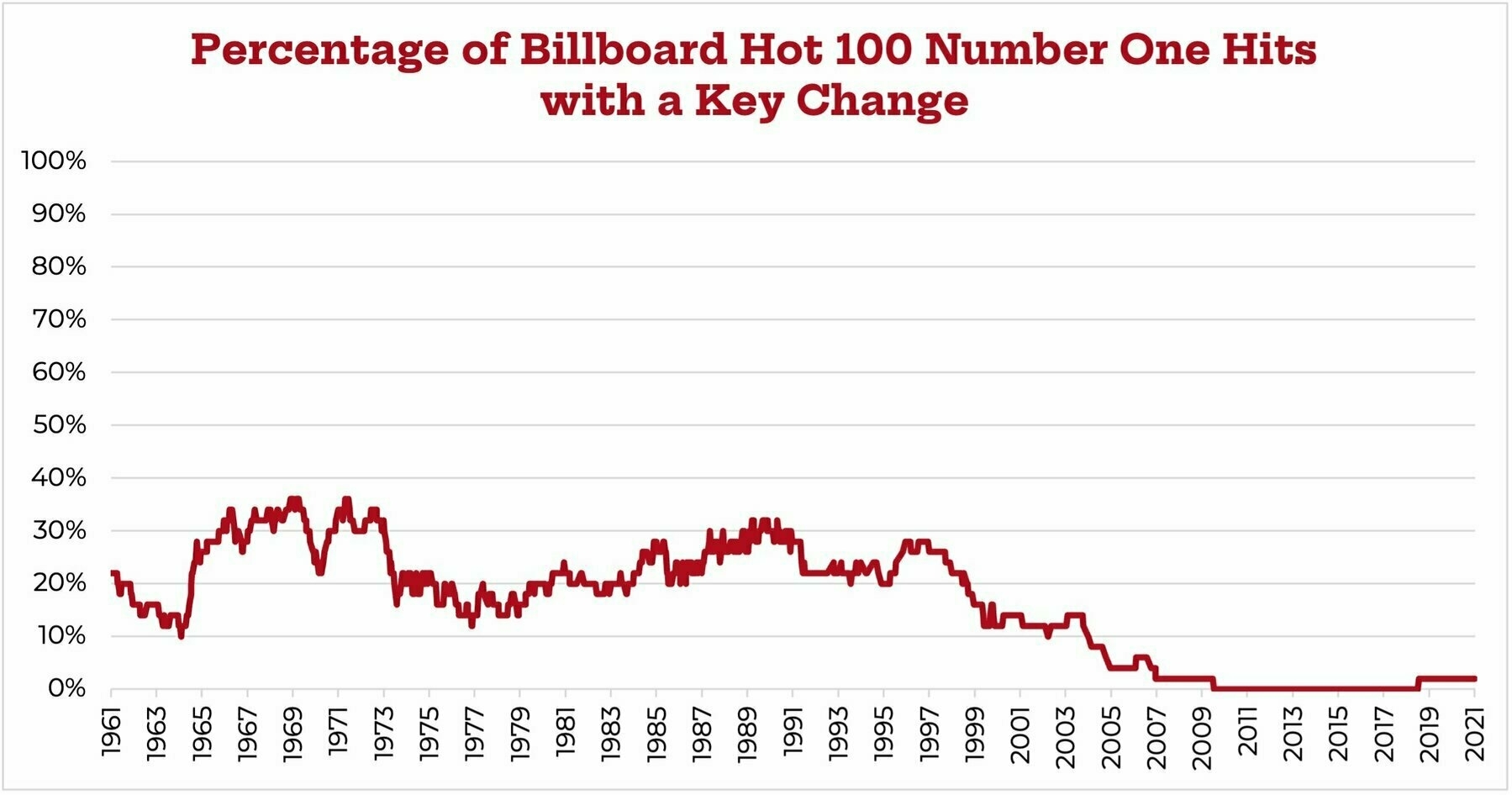

Both of the shifts can be tied back to two things: the rise of hip-hop and the growing popularity of digital music production, or recording on computers.

“The Death of the Key Change” by Chris Dalla Riva.

[Elon Musk’s] bigger problem is that he does not seem to know what he bought. There is little hope of Twitter becoming a “common digital town square,” as he put it in a recent letter to the advertisers. Instead Twitter, like all social media, is a “discourse-themed video game”. Specifically, it is a multiplayer online battle arena, where competing networks of accounts (informally led by influencers and blue checks) do battle. Luckily for Musk, there has been an enormous amount of experimentation with this genre of online games over the past few decades, and there is a clear winner of a business model: freemium with micropayments.

-Jon Askonas in this smart piece for Unherd called “Elon Musk doesn’t understand what he‘s bought.”