2022

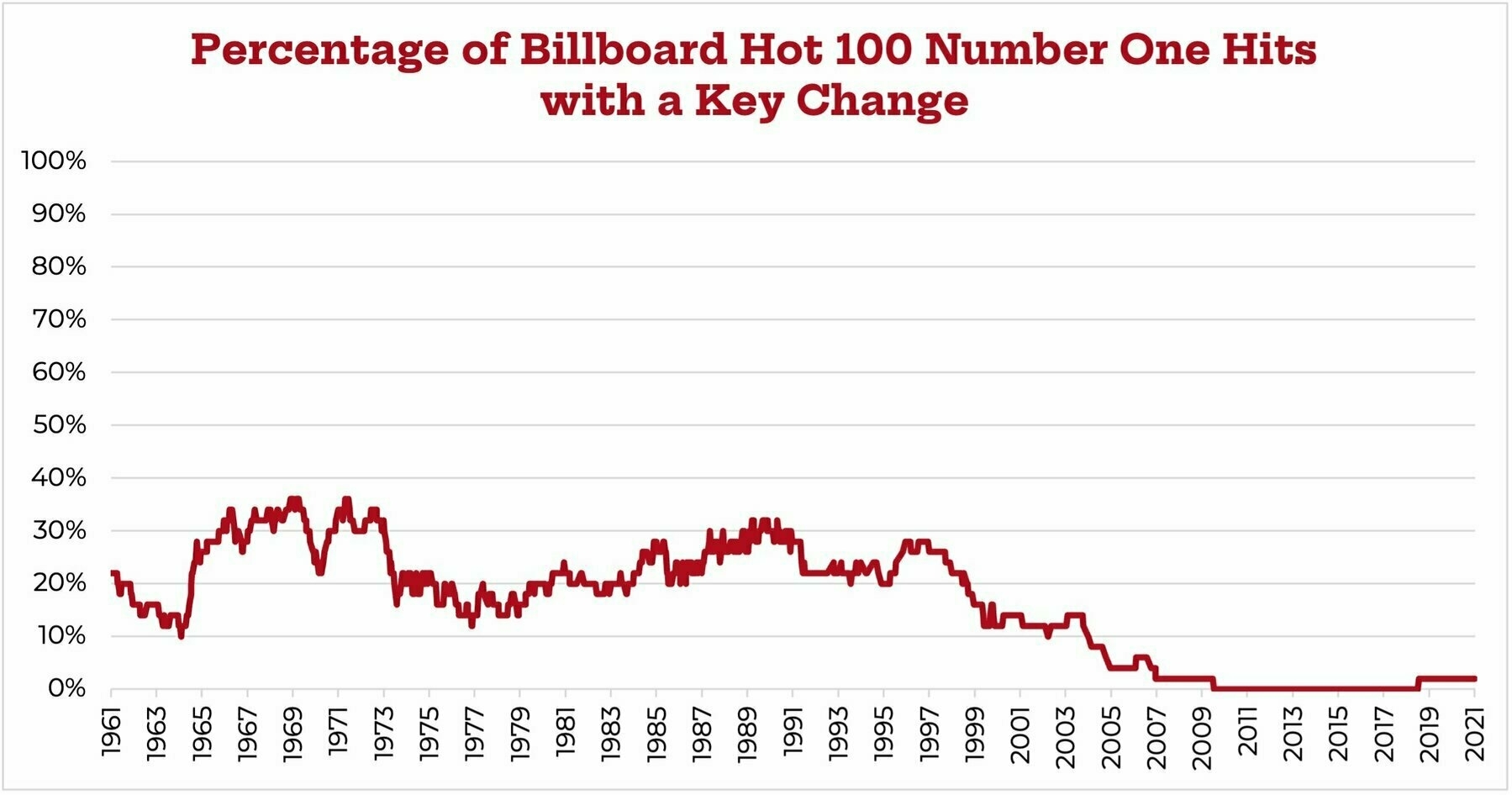

Both of the shifts can be tied back to two things: the rise of hip-hop and the growing popularity of digital music production, or recording on computers.

“The Death of the Key Change” by Chris Dalla Riva.

[Elon Musk’s] bigger problem is that he does not seem to know what he bought. There is little hope of Twitter becoming a “common digital town square,” as he put it in a recent letter to the advertisers. Instead Twitter, like all social media, is a “discourse-themed video game”. Specifically, it is a multiplayer online battle arena, where competing networks of accounts (informally led by influencers and blue checks) do battle. Luckily for Musk, there has been an enormous amount of experimentation with this genre of online games over the past few decades, and there is a clear winner of a business model: freemium with micropayments.

-Jon Askonas in this smart piece for Unherd called “Elon Musk doesn’t understand what he‘s bought.”

The distinctively modern feature of totalitarianism is that it combines a radically artficialist ideal with a radically organicist ideal. The image of the body comes to be combined with the image of the machine. Society appears to be a community of all whose members are strictly interdependentent; at the same time it is assumed to be constructing itself day by day, to be striving toward a goal—the creation of a new man—and to be living in a state of permanent mobilization.

Claude LeFort, “The Question of Democracy” in Democracy and Political Theory (1989).

An article in Vogue by the son of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. on the new corporate activists.

Stakeholder theory as a way of seeing old things in a new light

Feb 9, 2022We have a host of big American companies that are doing it right from the standpoint of all their constituents–customers, employees, shareholders, and the public at large. They’ve been doing it right for years. We have simply not paid enough attention to their example. Nor have we attempted to analyze the degree to which what they instinctively do is fully consistent with sound theory.

–Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman, In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies (New York, NY: Warner Books, 1983), XX.

Overheard at an academic conference

Feb 8, 2022“I remember I was starting up an escalator in a hotel and there were two young professors I didn’t know in front of me, except that I overheard that they were talking about me,” Henry Manne said in an oral history interview in 2012. “One of them said to the other one, ‘Aw, no, he’s not a conservative kook; he’s like Milton Friedman.’ At that point, I knew that the world had changed. If it had reached the level where Milton’s popularity and influence was now resurrecting my reputation, it was of big importance.”

Fink's letters

Feb 4, 2022Do Larry Fink’s annual letters make a difference in the way big corporations do business? One study showed that in firms where Blackrock owned at least 5 percent of the outstanding shares, the company was 22 percent more likely to use language that reflected Fink’s letter in their disclosures to the SEC. So says a study from accounting scholars published last year. My guess is that they are even more influential than that, especially in ways that can’t be so conveniently accounted for. Is it surprising? Perhaps not if you take into account that Fink’s first letter from 2012 stated that one of his intentions was to make proxy advisory firms—the companies, largely hidden from public view, that set the agenda and norms at annual shareholders meetings—less relevant. Here’s what he said ten years ago:

BlackRock’s approach to corporate governance can be described as value-focused engagement. We reach our voting decisions independently of proxy advisory firms on the basis of guidelines that reflect our perspective as a fiduciary investor with responsibilities to protect the economic interests of our clients.

History has a way of repeating itself, in a different form.

Feb 3, 2022

Although about 7,000 mergers were completed in 1968, fewer than 3,000 mergers were consummated in 1974, the fewest in more than 15 years. As of this writing–late 1977–the investment banking community continues to beleive that the merger and acquisition ways of the sixties are gone forever. Maybe so, but forever is a very long time. Besides, history does have a way of repeating itself, in a different form. Consequently, there is no way to know at this time what vogue, rage, craze, hue, or adaptation the merger game will assume at the end of the seventies and in the early eighties. But one thing seems certain. The game will be with us and could very will accelerate in the years ahead.

Don Gussow, The New Merger Game: The Plan and the Players (New York, NY: Amacom, 1978), 2-3.