2020

I have had occasion recently to discuss the concept of self-regulation and how this may inure to the benefit of the public investor as well as those in the brokerage community. It is in this context that I would like to invite your attention to an area which has been of real concern to the Commission. Increasingly, public investors are being asked to invest in what we refer to as “shell” corporations. These companies have little or no assets, little or no management or operational capacity and, obviously, little or no future. They are marked by a lack of financial and other information and they involve extremely high investment risk. Trading in a shell corporation usually has the following history. First of all, a promoter will purchase the outstanding sleeping shares of a publicly-owned corporation, a shell, for use as a holding company. Suppose we call this sleeping company South Sea Bubble of 1969. Since South Sea Bubble of 1969 is already incorporated and publicly owned, it affords immediate access to the public marketplace. Following the cquisition the promoter merges into the shell a private corporation, and usually one in which he has a controlling interest. As a dividend, the original shareholders in South Sea Bubble of 1969 now receive certificates representing their pro rata share in the new corporation. Shortly thereafter these same shareholders begin to receive letters, news releases and even annual or quarterly reports describing discoveries by, acquisitions of and projected sales by the formerly dormant corporation. Unfortunately it has been our experience that almost without exception these reports prove to be false.

Remarks of Hamer H. Budge, Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, before the National Security Traders Association in Boca Raton, Florida, October 19, 1969.

Corporation words

Sep 23, 2020The principal sources for the development of the corporation in the ancient world come from ancient Roman law. There are a handful of key terms.

One is collegium. It was used to refer to guilds, social clubs, religious groups, burial societies–things like that. If Plutarch’s life of Numa Pompilius has any merit, it seems as if this could be traced back to the beginnings of Rome itself. The collegia become more significant much later when the emporers surpressed and regulated them. Small corporations concerned even with such innocuous things as putting out a city’s fires had become known to rulers like the emporer Trajan and Pliny the Younger as sources of rival political power. Roman collegia seem to have possessed some legal personality. (See Jonathan S. Perry, The Roman Collegia: The Modern Evolution of an Ancient Concept (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2006), 6-7.)

Another word is societas, which Lewis & Short define as a fellowship, association, union, community, society (implying union for a common purpose; cf.: conjunctio, consociatio; and not a mere assembly; cf.: circulus, coetus; conventus, sodalitas;). There is some obvious overlap between these words, but the distinctive emphasis of societas is that it primarily refers to a partnership.

The final word was universitas, which as the English cognate implies meant simply “the whole.” Another meaning in Roman law was, according again to Lewis & Short, “A number of persons associated into one body, a society, company, community, guild, corporation, etc.”

These different Latin terms took on layers of meaning in the Middle Ages, particularly in ecclesiastical canon law, and played a role in disputes over political theory in the early modern period.

Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. Priorities for Action: Final Report. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973. (H/T Chad Wellmon)

Nike In the Global Economy, a speech by Nike founder and CEO Phil Knight on May 12, 1998 at the National Press Club.

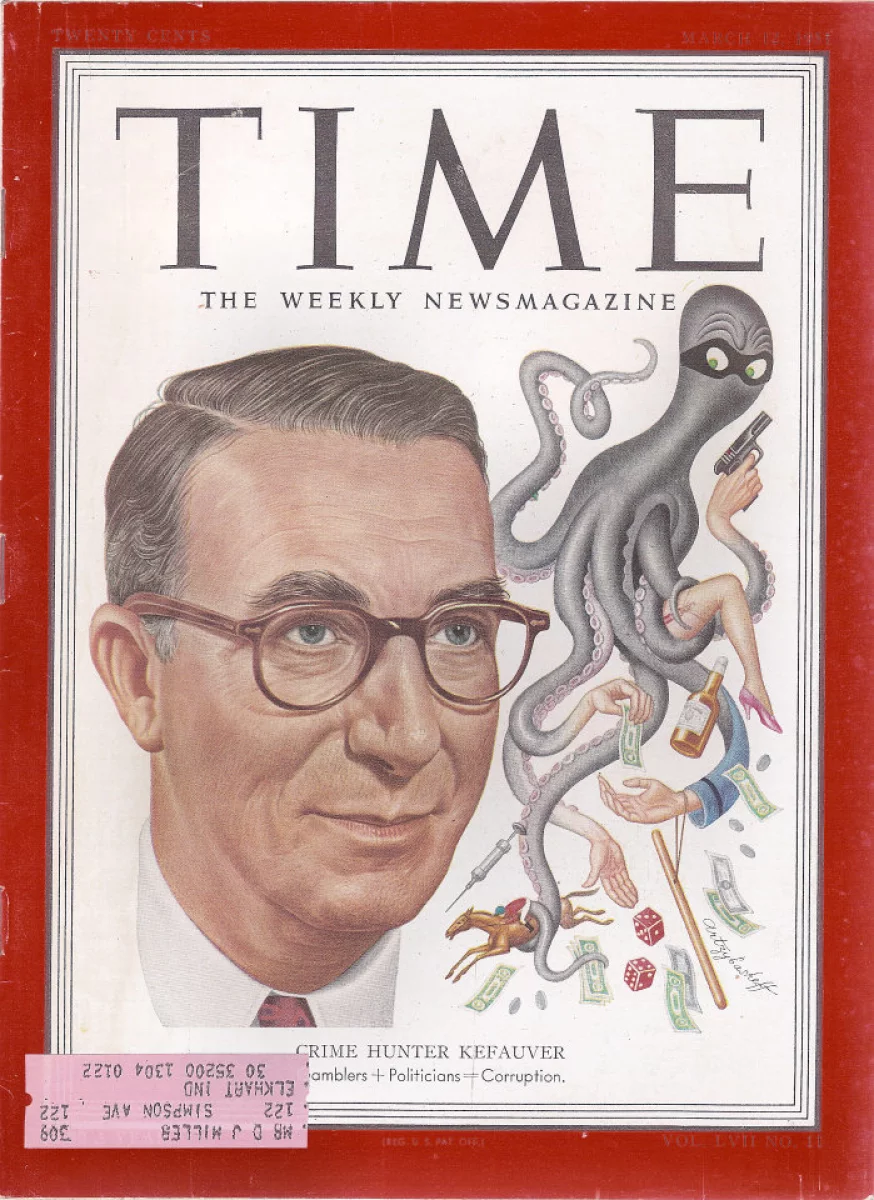

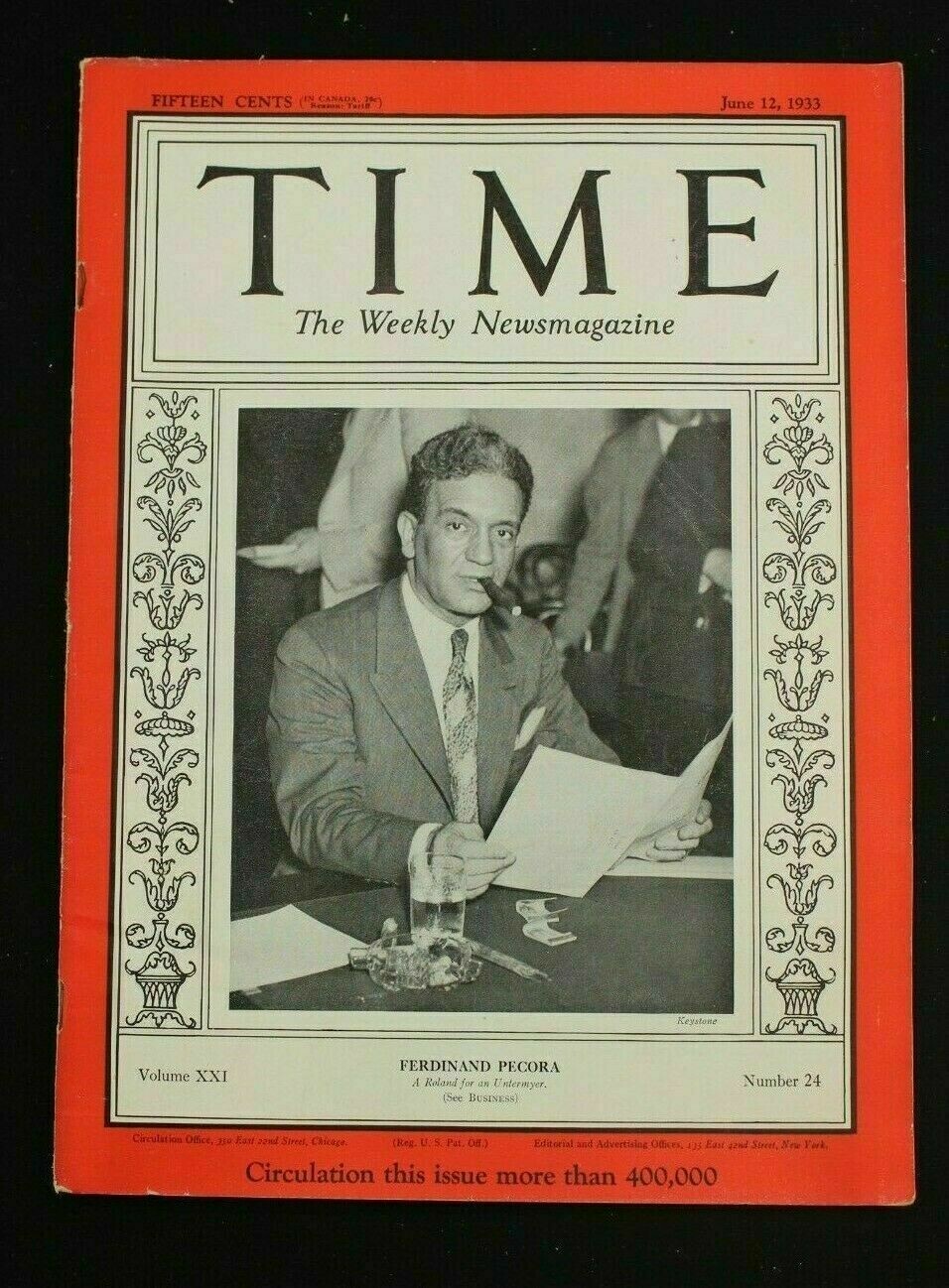

Ferdinand Pecora. Cover of Time on June 12, 1933. He became the face of the Pecora Commission, which provoked a reckoning with corporate governance in the early 1930s.

Protests against Dow Chemical’s production of napalm for the war in Vietnam enveloped the company in the late 1960s.

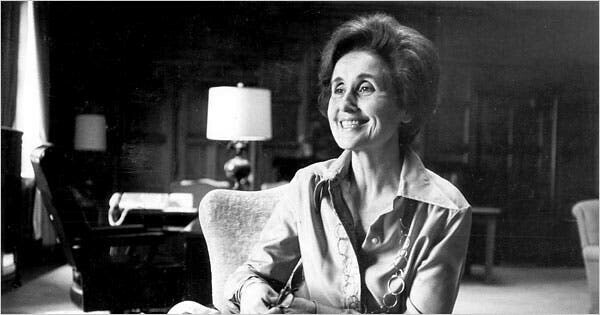

Juanita Kreps, Secretary of Commerce under Jimmy Carter between 1977-1979. She proposed a social performance audit for big business but was quickly forced to walk it back.

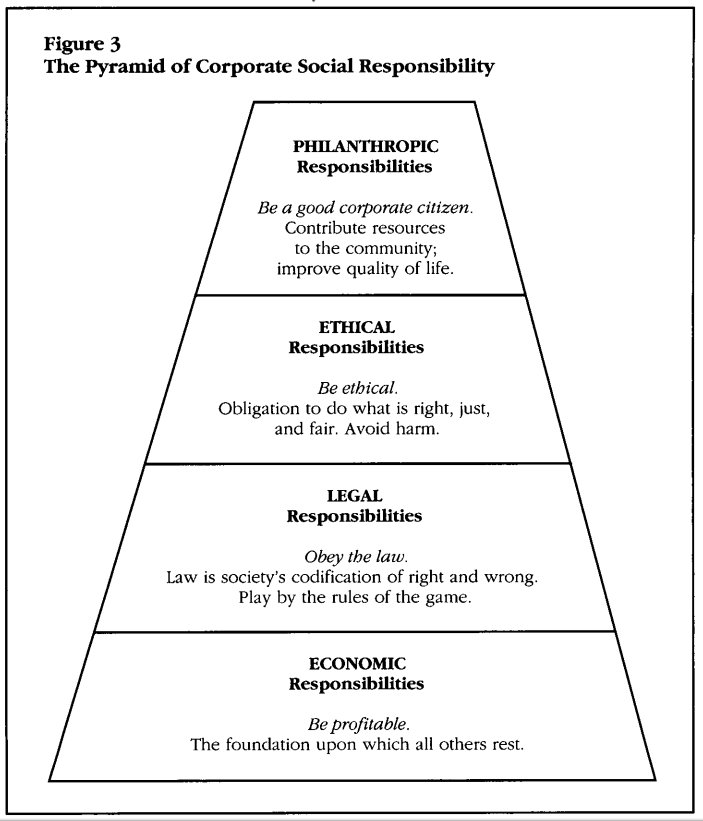

From Archie Carroll, “The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders,” Business Horizons (July 1991).